Background information and frequently-asked questions about coral reef restoration and the approaches taken by RRAP to develop tools to enhance the natural resilience of the Great Barrier Reef.

Climate change is widely recognised as a key threat to the Great Barrier Reef. The accelerating negative impacts of climate change threaten to overwhelm natural rates of reef adaptation. These threats include:

increasingly frequent and severe coral bleaching

increasingly frequent and severe and weather events, such as cyclones and floods

ocean acidification.

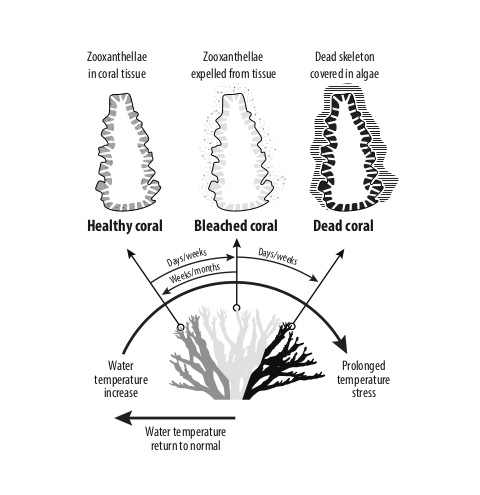

Corals have a mutually-beneficial relationship with microscopic photosynthetic algae (zooxanthellae) that live in their tissues.

Corals provide the algae with a protected environment and compounds needed for photosynthesis. In return, the algae provide much of the nutrition for the coral.

When the water temperature exceeds that normally experienced on the reef, algae are lost from stressed coral, leading to the white appearance that is termed bleaching.

If the heat stress is not too extreme, and water temperature returns to normal, it is possible for the corals to regrow their algae, and for the bleaching to be reversed, although health effects can be felt several years following recovery in some species.

With prolonged or extreme temperature stress, bleached corals will die.

The ocean’s chemistry is significantly changed when carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean: CO2 reacts with seawater, producing acid, which reduces coral’s capacity to build skeletons.

There are already some very promising reef restoration and adaptation measures, which may help buy time for the Great Barrier Reef – and other coral reefs in Australia and around the world – while the nations of the world reduce carbon emissions to sustainable levels, and global temperatures stabilise.

These are at different stages of development, and most need further research. In addition, methods to affordably scale up the technology for a significant, positive impact on the Reef ecosystem need developing. Building the Reef’s resilience to increasing water temperature, and other stresses, is complex and challenging.

The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program is working with different groups with a stake in the Reef – as well as Australians generally – to better understand how they see the risks and benefits of restoration and adaptation actions.

This will inform planning and prioritising of reef restoration measures, to ensure the proposed actions meet ecological and community expectations. The aim is to create a suite of acceptable measures that can be used for medium to large-scale reef restoration and adaptation.

Coral reefs are in decline worldwide. Climate change has reduced coral cover and surviving corals are under increasing pressure. Rising ocean temperatures and marine heat waves led to mass coral bleaching on the northern and central Great Barrier Reef in 2016, 2017 and 2020, compounded by cyclones and outbreaks of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish.

The frequency and severity of bleaching events is forecast to increase, in line with climate change predictions. Many corals already live close to their temperature tolerance limit and their ability to naturally adapt to increasing temperatures may not be sufficient given the magnitude and rate of global warming.

Despite the alarming outlook, the Great Barrier Reef still has high biodiversity, natural beauty and resilience. Commitments by governments to the targets of the Paris Climate Agreement could limit global warming to between 1.5°C and 2°C above pre-industrial levels (noting the Reef has already warmed by ~1°C). This gives us a window of opportunity to develop additional actions to support the resilience of coral reefs and to sustain their values and services.

RRAP is investigating ways to assist the Reef’s capacity for recovery and adaptation. The ultimate aim is to help protect coral species that provide critical habitat for 35 percent of the world’s fish, thousands of other marine species, and support livelihoods and economies worth hundreds of billions.

RRAP aims to take an integrated three-point approach to intervention to help the Great Barrier Reef resist, adapt to and recover from the impacts of climate change:

The program’s focus will be on protection and adaptation to prevent or minimise degradation and thus the need for restoration.

Global emissions reduction remains the most important action to minimise the impact of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef and other coral reefs of the world. However, even if global warming can be kept within 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial (the most optimistic goal of the Paris Climate Agreement), the world is set to warm another 0.5 degrees Celsius in the coming decades.

Because corals already live close to their temperature tolerance limit, this amount of warming will likely be too much for many sensitive coral species, including those that build important fish habitat. Emissions reduction, on its own, is no longer enough to guarantee the survival of the Great Barrier Reef as we know it. Safeguarding the Reef requires new interventions in addition to strong carbon mitigation and best-practice conventional management.

The additional warming the Reef will experience will depend not only on the latent warming already in the system, but also future emission trajectories. RRAP has evaluated the costs, feasibility and risks across multiple scenarios: climate change trajectories and social/economic futures. The Reef will have its best chance of maintaining biodiversity and ecological value if additional warming can be minimised and if people continue to care about the Reef and support its management. If global warming exceeds 2°C above the pre-industrial level, we will need to consider more radical interventions and measures of adaptation to build resilience. RRAP is evaluating a range of potential interventions including large-scale cooling and shading techniques and developing enhanced, heat-resistant corals to help increase reef adaptation to the changing conditions. Taking these approaches to protect key species in key target locations could maintain critical Reef values under less favourable climate scenarios. Importantly, CO2 mitigation and continued water quality management, crown-of-thorns starfish control and no-take areas will be more important than ever, and the prerequisite for a successful reef adaptation program.

RRAP interventions would aim to harness the Reef’s natural processes of larval dispersal to help spread resilient species or populations to reefs that urgently need climate tolerance. Where possible, we would help the Reef help itself. A small subset of the Reef’s 3000 individual reefs can help colonise corals on large areas of the Reef in a short time. RRAP research includes understanding and designing strategies for when and where RRAP interventions would be most effective. RRAP is focused on the recovery and survival of coral species that serve key ecological functions and underpin multiple Reef values. These include species that build important fish habitats. In addition to using natural Reef processes to help us scale up interventions in key areas, RRAP is working closely with engineering and technology sectors to develop innovative deployment solutions that can be delivered cost effectively at scale.

Corals have adjusted and adapted to their environment over decades to millennia. For example, corals in the Persian Gulf survive temperatures that are too extreme for coral species elsewhere, while certain coral species naturally tolerate more acidic (lower pH) water. On the Great Barrier Reef, temperatures vary by several degrees from north to south, and large temperature differences also exist within reefs between habitats and depths. The thermal tolerance of corals reflects their local temperature environment. This means corals in the northern Great Barrier Reef bleach at higher temperatures than those to the south. With rapid global warming, the key question is whether rates of natural adaptation are fast enough to keep up.

Adaptation can occur through a variety of ways and can be fast under the right conditions. Genetic adaptation occurs through changes in the organism’s DNA. Epigenetic changes involve modifications to the chemical switches on the DNA and can sometimes be passed from parents to offspring. RRAP aims to understand how adaptation in stress tolerance can be harnessed and enhanced over short time frames to help coral become more temperature tolerant.

The current rate of environmental change, and back-to-back bleaching events in 2016, 2017 and 2020, raised concerns that most reef-building coral will not be able to adapt fast enough. Recent research has found the Reef’s resilience may already be impaired with significantly reduced rates of coral recruitment and recovery following the bleaching events. Ultimately, this could result in a catastrophic loss of coral. Because corals build habitats and reef structure, they are foundational for much of the Reef’s biodiversity. Losing coral therefore means losing functions, and consequences could be devastating for all reef life and the people and economies who depend on it. The result could be a Reef with few ecological, social and economic values intact.

The Great Barrier Reef is home to around 600 different species of corals, many of which serve different functional roles. For example, some coral species are important as fish habitats, while others promote reef recovery after disturbances. Loss of coral means loss of habitat and food for fish, themselves potentially also directly impacted by climate change. This can lead to changes to the ecosystem, for example an increase in seaweeds that make it difficult for coral larvae to recruit to the reef and for adult corals to survive and recover. RRAP will explore solutions that will assist the recovery and survival of coral species that serve both key ecological functions and underpin multiple Reef values.

Conventional coral reef management on the Great Barrier Reef is currently focused on protecting reefs through zoning, managing and improving water quality and managing the populations of coral-eating crown-of-thorns starfish. These efforts remain critical to support reef recovery between bleaching events and storms. However, the gain in reef resilience from conventional efforts, even if they are intensified, cannot compensate for the stress caused by more frequent and severe bleaching events. In short: climate change will increasingly affect the Reef’s natural resilience despite the best conventional management efforts.

Keeping the Reef healthy in the future will require a multi-pronged strategy that combines:

The Great Barrier Reef and all other coral reefs in the world are changing as a result of impacts from human activities including climate change – with or without our best interventions. RRAP aims to provide solutions to help the Reef help itself, to maintain the ecological functions and species that support biodiversity, tourism and fisheries and give the Reef the best chance of survival in the future.

The Great Barrier Reef is home to many thousands of species, so the challenge will be to identify the species that most urgently need help while considering what species provide values for the ecological health of the Reef and society. Some species of coral that are homes for fish are also the most sensitive to climate change so they should be considered a priority.

Some species are seen to play more important roles in ecosystems than others. This importance is of course judged by people and relate to whether species support functions that underpin biodiversity and ecosystem services. RRAP will work with Reef stakeholders to develop a set of criteria against which we will develop strategies and alternatives for interventions. This includes the evaluation of “ecosystem engineers” (e.g. coral species that build structure and habitats), “keystone species” (which impact on other species), and species that have high aesthetic, recreational or commercial values.

Genetic engineering of corals or their symbionts is one of many ways we might help corals become more tolerant to bleaching in the future. Genetic engineering provides a way to precisely edit specific genes that regulate for heat resistance or to insert genes that increase heat tolerance or disease resistance. However, the application of genetic engineering solutions for the Reef will require extensive research and development, assessments of benefit and risk, plus legislative approvals that do not currently exist. RRAP will consider all options that meet the criteria of providing a net benefit for the Reef at acceptable levels of risk, scale and cost. Most of the currently proposed interventions will not involve gene technology. For example, we can consider to move warm-adapted corals or their offspring to naturally cooler places or we can use other assisted evolutionary processes to promote heat tolerance in corals. Starting the research and development and rigorously testing these tools soon gives us the best chance to use them safely and effectively in the future if or when we need to.

The right time to start any new intervention is when the risk of inaction is greater than the risk of action. As climate change intensifies, so do impacts on the Reef. Delaying the use of new interventions means foregoing opportunities to save species and values. But acting too fast with untested intervention can also pose risks from unknown side effects. To strike the right balance of minimising risk and maximising opportunity, RRAP must begin researching and development of the most promising interventions now. The longer we wait, the more expensive and difficult it will be to successfully intervene at any scale, and the greater the risk the window of opportunity will close. All new interventions will be rigorously assessed and tested, in close consultation with partners and stakeholders. The result will be an expanding set of interventions that can be ready for safe implementation if or when they are needed.

The interventions being investigated by RRAP aim to enhance the resilience of coral reefs but vary in their associated risks. For example, enhancing corals using assisted gene flow and assisted evolution represent manageable risk because they use genetic material already present on the Reef. Assisted colonisation that involves importing coral species from outside the Great Barrier Reef may carry greater ecological risk than other approaches. A full understanding and evaluation of risks is a key component of RRAP and will be evaluated from ecological, social and economic angles. They will be assessed against the risk of ‘doing nothing’ or delaying interventions. Predicted benefits will be evaulated against the chances of any potential negative outcomes. These analyses will provide clarity for all, inform a prioritisation of techniques for technological development, decision-making, facilitate a license to operate, and promote stakeholder engagement.

Our vision is that RRAP will help protect values that are critical for the health and ecosystem function of the Great Barrier Reef – its rich biodiversity, continued status as a World Heritage Area, and a place that continues to support recreation, culture and a multi-billion dollar economy. The Reef is a natural asset valued at $56 billion, an ecosystem of global significance and a critical part of the Australian national identity. By working closely with partners and stakeholders to identify interventions that sustain both ecological functions and social and economic values, RRAP will help sustain this asset for Australia and the world.

An essential part of the planning and feasibility assessment phase will be to understand not only the likely benefits and costs of possible interventions but also the ecological, economic and social risks. To do this requires a collective effort of all Reef stakeholders. RRAP will actively engage and consult with all people connected to the Reef. It will build strong partnerships between researchers, government agencies and the wider community, including Traditional Owners.

A range of reef restoration approaches have been applied on reefs around the world for decades. They have been successful in, for example, increasing coral cover or reducing algal cover on very small scales. Many projects have included gardening of corals in land-based or marine nurseries, and more recently laboratory reared coral young have been used. Despite positive reports of many restoration efforts, the cost and effectiveness of many interventions remain unclear.

RRAP is capitalising on existing knowledge and aiming to provide a step-change in the cost and scale by which active interventions can be delivered on coral reefs. To achieve this we will be working closely with the engineering and technology sectors to develop innovative deployment solutions that can be cost-effectively delivered at the required scales.